The Children of War

In my recent book, El crimen de la guerra (soon to be published in English as War Is a Crime against Humanity), I propose that war is no longer a viable means of solving differences among nations, regions, factions and political systems. There are any number of reasons that the world should start seeing war for what it is—a crime against humanity—and begin searching for ways of preventing and prohibiting it around the globe, and bringing its authors to justice in a court of law, no matter who they may be. Among other factors to be considered, the proportion of fatal civilian to military casualties has been inverted compared with old-time wars. The rate used to be one civilian death for every nine military deaths (which, even so, seems a fairly high proportion of “collateral damage”), while today, the average rate is nine civilian war fatalities for each combatant killed. In addition to this, there is always the latent threat of any conflict’s spreading to neighboring regions or countries and, thus—with any intervention of the major powers—continuing to spread, generating a large-scale war, with the ultimate threat that this signifies for the entire world in the Nuclear Age.

But the soundest reason to change our mindset and no longer accept war as “a viable political tool” is the following fact: In the last decade, some two million children (many of them under the age of ten) have died around the world as a result of the 30-odd armed conflicts currently under way. According to the International Red Cross, as many as 12 million other children have been wounded or mutilated for life. If we want to bring these figures into perspective, that’s 1.4 million children a year who have died or been wounded in the conflicts taking place around the world over the course of the last decade. By comparison, during the entire decade that the United States was fighting in Vietnam, total US troop fatalities came to 58,209, with another 153,000 American troops being wounded—figures that clearly pale by comparison with the massacre that innocent children are suffering today in conflicts worldwide (some 3,835 children killed or injured daily).

In light of such data, it should remain clear—for any sane person, at least—that war has changed, not only so specifically, but also so horrendously, that every right-thinking man and woman in the world should at this very moment be making the firm commitment to do everything in his or her power to make that mind shift and to institute, at a general and global level, a clear vision of war as a crime against humanity, triable and punishable under law through institutions specifically created for this purpose, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The nature of war has been changing ever since World War II. The horror of that global conflict, in which more than 60 million people died, many of them civilians who were the victims of indiscriminate bombing, marked a new direction toward an ever more savage world where the rules of earlier wars—in which two or more armies met and struggled on a more or less clearly bounded battlefield and in which “collateral damage” was less than one civilian death for every ten soldiers who lost their lives— became much less well defined. There is no incident more indicative of this trend toward increased savagery than the decision of then-President Harry S. Truman to drop two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of the Second World War, killing, in the wink of an eye, tens of thousands of innocent civilian men, women and children, in a true act of extermination, with the excuse of ending the war quicker and “saving American lives.”

True, since that tragic and tremendous moment in human history, a common and universal effort has been made to prevent—mainly through the United Nations, which was born as a consequence of World War II and its devastating effects—any other global-scale conflict. Clearly, the major powers realized at some point, after Washington dared make use of weapons of nuclear mass destruction for the first and only time in the world, that what was on the table in a third world war was no less than the survival of the human race itself.

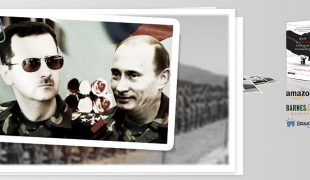

Nevertheless, instead of taking full advantage of the impetus provided by the founding of the UN and the end of the worst war in history as the starting point for a serious search for world peace, in which world leaders would use their power to guarantee peace and promote peaceful solutions to regional differences, the major powers have taken part in an interminable series of geopolitically limited armed conflicts in which supporting one or the other of the belligerents works to their own geopolitical benefit. Even in the best of cases, main players on the global scene have simply ignored certain conflicts in which they have been unable to detect any advantage for themselves, not intervening on one side or the other, but neither making use of their political, diplomatic or military resources to pacify such situations and lead the warring sides to the negotiating table and, ultimately, to signing peace treaties.

Worse still, the arms industries of the world’s leading countries are to be blamed for escalating such assaults on world peace, perpetrated in practically every region of the globe since the end of the Second World War and up to the present day, since even while these prime countries have sometimes urged belligerents to seek peaceful solutions, their arms makers (and traffickers), frequently in connivance with their own governments, have provided the warring sides with abundant, cheap, powerful and sophisticated weaponry. It would hardly appear a coincidence that of the world’s six largest arms exporters, five are permanent members of the UN Security Council, with exclusive decision-making power over use of force and peace-keeping operations around the world, in addition to having veto power over any resolution presented by the rest of the nations in the General Assembly. These five countries, then, are the key to the search for enduring world peace.

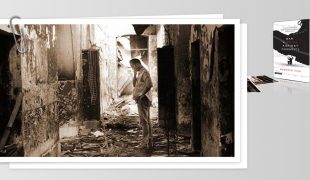

The explicit threats posed by the way in which war is made today don’t emerge solely from the fact that we live in an ever less ethical world, a world ever less respectful of proper practices and of law as the framework for civilized society—although these are, without a doubt, relevant factors contributing to the mounting chaos and violence that we are experiencing—but also from the fact that the nature of wars as such has morphed into something without any of the clear-cut characteristics that it once exhibited: The thirty-odd wars that are today exerting an impact on human beings around the world are ethnic, regional, civil and/or revolutionary against the regimes ruling the countries involved. Seldom are they between states, or at least not just between states, but also involve guerrilla or terrorist groups that bring irregular combatants into the mix. They also mix rage and resentment with racism and fundamentalism. They pit military troops against clandestine movements that blend in with the civilian populations, and armed cells of fighters who occupy dwellings in residential zones. These are factors that remove combat from its traditional venues and introduce it into places where pitching a battle virtually guarantees more civilian than military fatalities, and that signify the destruction of the infrastructure and homes of common citizens, generating the urgent need for these people to flee and, from one day to the next, become “refugees”.

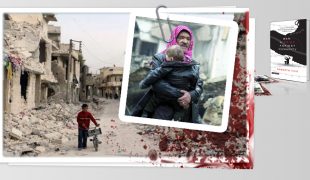

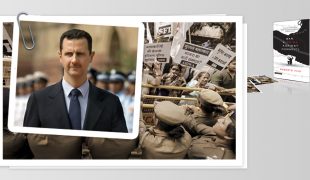

Neither, however, are civilian casualties in this new nature of wars always accidental. On the contrary, there appears to be an ever greater trend toward directly targeting civilians in war action—a tendency that also is often directed specifically toward targeting women and children. In Syria, the war drawing the greatest media attention right now, there have been frequent reports of sniper attacks on women and children walking in the streets, as well as of intentional bombings of schools and hospitals. Children in areas captured by Syrian rebels have additionally suffered the consequences of a policy imposed by the government of Bashar Hafez al-Assad of not permitting passage of humanitarian aid destined for these zones—even to the point of refusing “to allow even a mouthful of food” to get in. Since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, some 7,000 children have died as a result of the conflict, more than 1,600 under the age of ten. The “lucky ones” who have escaped the chaos in their own country now live as refugees in neighboring nations. Right now, there are more than a million Syrian refugee children and they form more than half of all refugees who have fled that country.

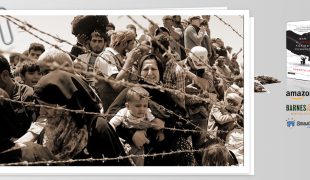

For anyone unfamiliar with the reality of war “refugees” around the world, that term may well stir images of folks being sheltered and cared for by the good Samaritans of friendly countries. But according to UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund), for the displaced people of Syria, the word “refugee” is fairly misleading. And UNICEF adds that those who are most vulnerable in the refugee camps are children, who are often exploited as beggars or are sexually abused. Nor are the Syrian refugees particularly welcome in the countries to which they have fled, since today, one in every ten Syrians is a refugee and in Lebanon, for example, one in every four inhabitants is a Syrian refugee. In Egypt, where, at last count, there were 125,000 Syrian refugees, some have been arrested en masse and deported back to their own country, despite international petitions sent to Cairo requesting clemency for them. Besides the more than 2 million Syrian refugees currently living in other countries, there are another 4 million, half of them children, who are displaced within their own country’s borders. And this is a pattern that is frequently repeated in the rest of the world’s current wars.

According to the NGO Children and War (www.childrenandwar.org) more than a billion children—or a sixth of the entire world population—are today living in armed conflict zones, or in areas that are currently emerging from a state of war. Children and War cites the renowned UN study carried out by Mozambican politician and humanitarian (and third wife of the late South African leader Nelson Mandela) Graça Machel, in stating that there are currently more than 18 million children living as refugees or otherwise displaced from their homes, and that more than 500 million children a year are somehow affected by mass violence.

But this mass attack on innocence doesn’t end with bombings, snipers, domestic and foreign exile, miscellaneous despots, terrorism and famine. There are children in many parts of the world today who are also suffering the trauma and indignity of being enslaved and pressed into service in both regular and irregular armies. At first, this practice was limited, more than anywhere else, to Central Africa (with the best known example being that of fugitive Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony, who has been formally indicted by the International Criminal Court for making use of African boys and girls in his combat groups not only as armed troops, but also as slave labor and sex objects for his men’s use). Today, however, according to UNICEF, “child soldiers” are participating in the majority of the more than thirty armed conflicts currently under way worldwide, in what is being seen as a growing and commonly widespread trend. UN estimates place at approximately 300,000 the number of children between the ages of 10 (or less) and 17, who are at present taking part in combat around the world. Among these child recruits, up to 30 percent are “girl soldiers” and it is they who are most vulnerable to sexual abuse both within their ranks and when captured by enemy combatants.

Unfortunately, none of these are “momentary” trends resulting from “emergencies of war”. UNICEF authorities warn that “Defining war as an emergency is too optimistic (since) it suggests that it will end. On the contrary, war is chronic.”

In writing of the report she prepared for the United Nations, Graça Machel warns that for children in war, “the physical, sexual and emotional violence to which they are exposed shatters their world. War undermines the very foundations of children’s lives, destroying their homes, splintering their communities and breaking down their trust in adults.”

According to Machel, “We treat bullet and shrapnel wounds, provide prosthesis for mine victims, house the displaced and refugees of ongoing conflicts, but how do we fare in providing those most vulnerable and least able to cope with the nutritional, environmental, emotional and psychological effects of conflict?”

There are organizations that are seeking to mitigate the damage: among them are UNICEF and the Red Cross, which have special programs through which to provide aid, shelter, and physical and psychological therapy to these “war children”. But there are also others, with much more specific missions, like Invisible Children (www.invisiblechildren.com), which began working in Uganda and later expanded its scope to other parts of Central Africa, not only by attempting to recover child soldiers, but also creating award-winning documentary films about the problem and putting together an intensive campaign to track down the nefarious rebel leader Joseph Kony, dismantle his organization, and place him at the disposal of international justice; or like Children and War, with headquarters in Bergen, Norway, which was jointly founded by that country’s Center for Crisis Psychology and by the Psychiatric Institute of London, whose mission is the detection and treatment of minors in crisis from the world’s conflict zones; or like War Child International, which has headed up projects in such war zones as Afghanistan, Burundi, Chechnya, Colombia, Congo, Ethiopia, Iraq, Israel, Kosovo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka and the Gaza Strip, with the aim of protecting, educating and seeking justice for child victims of mass violence, as well as providing them with training and psychological support.

The work these and many other groups dedicated to humanitarian aid in general and child protection in particular are doing is very intense, clearly focused, highly necessary, sadly insufficient and absolutely admirable. But it is not the definitive solution to the perennial problem of war and its effects on society as a whole and its future. The solution lies in creating a new awareness, a new philosophy, a profound change of attitude from the base of the human pyramid to the pinnacle of leadership, sufficient to allow us to accept, once and for all, that war is not only no longer viable, but that it is and always has been a crime against humanity, which threatens more all the time to destroy us as nations, as a world society and, eventually, as a species.

Just as important, in this sense—and among many others—as the humanitarian aid projects that we mentioned earlier are incipient efforts to expand, on a massive scale, the work of famous pioneers like renowned educator Maria Montessori, in the field of peace education. An innovative proposal, the ultimate goal of which is to build awareness so as to start building peace for the future, is the Nuremberg Fair, aimed at fostering peace education and helping it find its way to 500 million young people worldwide over the course of the next decade. The Nuremberg Fair proposes disseminating peace and justice education by recognizing the work of hundreds of peace educators from all over the world and providing them with incentives to present their methods and results in an annual competition that will grant awards to the ten most original initiatives as well as distributing them on an international scale. The first experience for this innovative international competition is slated for some time in the second half of 2014.

Today, before it’s too late to save the world, hundreds, thousands of initiatives of all kinds are needed in order to create a new pacifist awareness in the world, so as to help future generations de-glorify war, stripping it of its current mask of legitimacy and qualifying it as a crime against humanity. In the meantime, even the major nations, which define themselves as just, civilized and democratic, will continue violating, as they are doing today, the most basic rights of thousands of innocent victims and, above all, of the most precious and most vulnerable members of the world population: the children.