UKRAINE: A Cold War Retrospective

New York, March 9, 2014

This past week’s decision by the Crimean parliament to secede from Ukraine and join the Russian Federation took the international political crisis sparked by the arrival of Russian troops in Crimea to a new and ever more troubling level. Crimea announced that it would hold a referendum later in March to validate its lawmakers’ decision, but word from the region was that pro-Russian officials had already asked Moscow to move ahead with procedures to integrate the Crimean region into the Russian Federation and to provide its Russian-speaking residents with full official citizenship. The new leadership in Kiev and its Western allies immediately rejected any such move as illegitimate and said they would not recognize it.

The situation of Crimea is far more complicated than it might at first appear to be. Crimea is not merely a province of Ukraine. It is legally structured as an “autonomous republic” within the “unitary state of Ukraine”. What this means is that it has a so-called “Presidential Representative” serving as its governor and that it has a 100-seat parliament of its own (better known as the Supreme Council of Crimea). In a region where nearly 60 percent of the population is of Russian ethnicity, this system seems to have worked fine as long as Ukraine had a pro-Moscow government. But the violent protests that earlier this year ousted pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych—who had turned his back on a cooperation agreement with the European Union and instead accepted a US$ 15 billion bailout package that promised to significantly deepen his country’s ties with Moscow—changed all that, since the interim government that replaced him is seeking much closer ties with Western Europe and the United States. Meanwhile, Russia’s impetuous invasion of the Crimean region has helped the new Ukrainian leadership advance toward that very goal. On the heels of Moscow’s military action, the West has already pledged aid to Kiev at least equal to the Russian bailout promised to Yanukovych.

It’s hard not to suspect that fears fostered in the Crimean population of possible persecution of ethnic Russians by a new pro-Western regime—billed by Moscow as “Nazis and descendants of Nazis”—were kindled and exploited by both Russia and local authorities, who obviously had a great deal to lose in the face of swift changes in the political landscape. Russian military intervention in Crimea early this month (following massive saber-rattling maneuvers on Ukraine’s borders the previous week) and the de facto secession of Crimea and request for integration into the Russian Federation engendered by its parliament seem to make this abundantly clear, as do pro-Moscow demonstrations hastily organized in key Crimean locations.

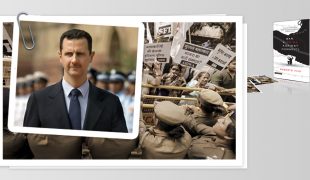

Russian President Vladimir Putin has insisted from the outset that his so-far bloodless invasion of Ukrainian borders is basically a “human rights mission” (preemptive protection of the rights of ethnic Russians in a neighboring territory). But in a later telephone conversation with US President Barack Obama, Putin is understood to have said he was exercising his right to “protect Russian interests” wherever they might be found.

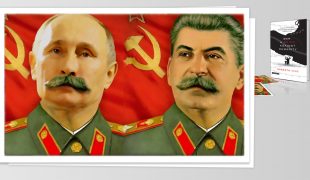

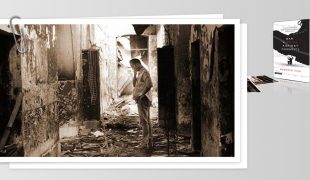

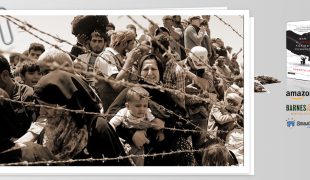

While Moscow is in the process of doing either of these things, there is another complication in the Ukraine situation that bears consideration: the plight of the minority Tatars in the Crimean region. The Tatars—a Sunni Muslim people who have embraced Islam since at least the 13th century—are the aboriginal people of Crimea, if today forming only 12 percent of that region’s population. Their history with Russia is a dark one. After imperial Russian annexation of Crimea in the late 18thcentury, the then-czarist regime instituted a policy of persecution in which Tatars were systematically slaughtered or exiled to Siberia, thus reducing the Tatar population in Crimea by two-thirds before the end of the 19th century. The Tatars fared no better under Communist Russia. Between 1917 and 1933, men, women and children forming more than half of the remaining Tatar population that resisted Sovietization under Russian rule were slaughtered, starved (since food was shipped out of the region to central Russia) or deported. And they were again deprived, persecuted, killed and deported under the brutal Stalinist regime a decade later, with Moscow accusing them of collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Today the Tatar population is scattered over a number of countries (notably Turkey, Rumania, Uzbekistan, Russia and Bulgaria), but as of the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 1980s, many Tatars have returned to Crimea only to find their traditional homes and land occupied by post-World War II settlers of Russian and other ethnicities. While they have made their peace with the situation and begun new and productive lives in their old homeland, given their history with their Russian neighbors, Tatars are clearly wary of any less than conciliatory policies emerging from Moscow. President Putin’s aggressive military backing of pro-Russian Crimean separatists, then, has made the Tatars at least as nervous as it has the new West-leaning Ukrainian authorities in Kiev. Now, once again, more Crimean Tatars live in Ukraine than anywhere else in the world and they are the largest Islamic group (an 80 percent majority among Ukrainian Muslims) in that country.

Still others fearful of what might happen in the future if Russia is not stopped now in Ukraine and driven back across its borders are the leaders of currently independent countries that fell under the domination of Soviet Russia during the years following World War II—Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic among them. Moscow used the same excuse—protection of the rights of ethnic Russians in Abkhazi and South Ossetia—for its invasion of the former Soviet republic of Georgia in 2008, leading to a nine-day war in which hundreds (including both soldiers and civilians) were killed and at least 1,300 were injured in the South Ossetia region. Despite Moscow’s “human rights” justification for that invasion, a half-decade later both Abkhazi and South Ossetia remain under effective annexation, with Russian troops still present to back Moscow’s claim to them.

What these Eastern European fears fail to take into account, however, is that there are very active political divisions currently at work in Ukraine that will eventually have to be ironed out by Ukrainians themselves. It is not a simple matter of that country’s having been held hostage by Moscow, as happened, for instance, when the former Soviet Union invaded Prague following widespread rioting against Russian rule in 1969. The fact is that just weeks before the latest developments in Crimea, Ukraine was in the throes of severe civil strife stemming from deep-seated divisions between significant opposing sectors of the population who either sided with deposed President Viktor Yanukovych in shunning the West and championing stronger ties with Russia or leaned toward the West, rejecting the government’s unilateral shift toward Moscow and clamoring for Yanukovych’s resignation. The fact that the latter group eventually won out doesn’t mean that those political divisions are likely to go away anytime soon. But it is up to Ukrainians to resolve them and any interference by either the Russians or the West in this sense, other than through diplomatic means, can only be viewed as illegitimate aggression by a foreign power.

US President Obama last week made this clear when he said that, in Crimea, Russia was “on the wrong side of history,” sagely adding: “There is a way for Ukraine to be a friend of the West’s and a friend of Russia’s, as long as none of us are inside of Ukraine trying to meddle…(and) certainly not militarily.” The US president’s public statements were an indirect appeal to Russia’s Putin to reconsider his rash action. He said that he disagreed with analysts who have suggested Putin was showing himself to be “strategically clever” by invading Crimea and thus putting Kiev on notice. On the contrary, Obama said, all Russia was doing was fostering grave concern among many other countries in the region, while creating a strong feeling all over the world that “Russia’s actions are violating international law.” In an apparent attempt to de-fuse the crisis, Obama added that “There have been reports that President Putin is pausing for a moment and reflecting on what’s happened.” The American leader also said that there was speculation that Putin was “listening to a different set of lawyers and a different set of interpretations, but I don’t think that’s fooling anybody. I think everybody recognizes that although Russia has legitimate interests in what happens in a neighboring state, that does not give it the right to use force…”

Unfortunately, no matter how sincere and ethically correct President Obama’s words might be, in the light of Washington’s illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003 and its consistent use of military force to underscore its geopolitical and commercial interests in far-flung locations around the world, such sentiments have a hollow ring, especially to the leader of a once equally powerful Russia who might easily question the moral capital of another world power that says, “Do as I say, not as I do.”

In spite of the seriousness of what has happened over the course of the past week or so in Crimea—there can be little doubt that Russia’s actions are more in line with Putin’s desire to reclaim and firmly grasp Russian influence in the former Soviet Bloc countries than with any concern of his with “human rights”, and that Moscow’s moves in places like Georgia and Ukraine are clearly, therefore, blatant acts of aggression—it is of utmost importance that the West, and especially the United States, not let hawkish far-right-wingers goad them into any sort of military response that might (and surely would) threaten world peace (such as it is, with more than 30 wars already under way), today and in the future.

While giving peace a chance is the best and most idealistic but also most realistic of reasons not to entertain any pseudo-heroic illusions about “sending Russia packing” in Ukraine, there are sound and factual grounds for eschewing military action from the outset that make even more sense within the framework of world peace. To start with, any thought of a military response to the Russian invasion of Crimea can only be based on overblown nationalism, political self-glorification and delusional false expectations (all of which have historically been causes of wars and, subsequently, of the crushing defeats of those who have applied them over and above cold logic). The United States—the only country even remotely capable of presenting a direct military challenge to Russia—is still reeling under the vastly miscalculated burden of is fictitiously-based wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and is in no condition to attempt to use brute force to make a well-matched Russia do anything at all in Moscow’s own back yard.

Furthermore, seen from a purely realistic standpoint, nothing affecting the United States either strategically or economically is at any real risk in Ukraine, no matter how President Barack Obama’s rightwing political rivals seek to push a tough hold-that-line military agenda. Make no mistake about it: The interest of American hawks in rattling their sabers in the president’s face is entirely self-serving and designed to undermine Obama’s public image—and that of his party—rather than to serve any legitimate US interests. On the contrary, by suggesting that it might be weak not to go head-to-head with Putin, the card US hawks are playing is potentially detrimental to American and world interests since any real attempt to contain the Russians militarily would involve the West and the entire world in an explosively dangerous situation.

Any tendency in Washington to claim that US credibility is reduced by actively seeking a diplomatic solution rather than stonewalling militarily and insisting that Russia pull back “or else”, surely finds its roots more in electioneering politics, cowboy fantasies and pure jingoism than in anything even vaguely resembling the true interests of the American people and the world at large. Americans and people in the West as a whole need to understand that a military response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine would have far-reaching and dire consequences for world peace—unacceptable consequences in the Nuclear Age, which were clearly comprehended and thus carefully avoided by both Washington and Moscow, despite their mutually aggressive rhetoric, throughout the entire Cold War era. And as such, they need to reject (and punish at the polls) any crackpot politician who even vaguely suggests military retaliation as a “viable alternative”.

That said, Russia—and, more specifically, Putin—needs to be taken to task for its illegitimate invasion of Ukraine’s territory. And this situation once again points to the ridiculous limitations that the major world powers have imposed on key world institutions such as the United Nations (UN) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, Russia can effectively veto and block any resolution by the rest of the world condemning or sanctioning it for its actions in Ukraine. Moreover, while Russia has signed the Rome Statute creating the ICC, it has yet to ratify it, which means that while the court might conceivably bring charges of aggression against Moscow and Putin for the Crimea invasion, if Russia denied (as it surely would) the court’s jurisdiction, any such legal action would be rendered null and void. If world peace is ever to be consolidated, these throwbacks to an imperialist age need to change drastically in the interest of global governance and justice.

Still, there are other ways to bring worldwide pressure against Russia, which are a matter of putting world peace and resistance to further aggression above commercial and political convenience. And it is a relief to see that, for the moment at least, this is the path that the United States, as world leader, is advocating. US Secretary of State John Kerry reflected this attitude this past week when he said that, “Russia has made a choice and we have stated clearly that we believe it is the wrong choice…Russia can now choose to de-escalate the situation. We are committed to working with Russia, but together with our friends and allies, in an effort to provide a way for this entire situation to find the road to de-escalation.” Kerry further called on Russia to take up direct talks with the Ukraine government, in order to find a peaceful bilateral solution to the crisis.

Until the day that world institutions are structurally reformed and empowered for the creation of a more just and peaceful world, a unequivocal commitment to a diplomatic solution for Ukraine coupled with strictly concerted moves to effectively isolate Russia both diplomatically and commercially—until such time as it decides to rethink its policy of invoking military aggression to force its neighbors to do its bidding—are the only feasible tools currently available for seeking a remedy that does not further endanger world peace.